Currently, we are exploring Japanese horror on Carnal Extremities and, with the help of our guest Amber T who joined us to discuss TETSUO: THE IRON MAN (1989), we hashed out what defines J-horror and how it’s related to the burst of the economic bubble in Japan during the late 80s/early 90s. Last night, I was fortunate enough to catch a Kurosawa Double Feature of CURE (1997) and PULSE (2001) presented in 35mm at the New Beverly Cinema and all I could think was that nothing so clearly paves the way for J-horror’s roots in economic despair as Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s CURE (1997).

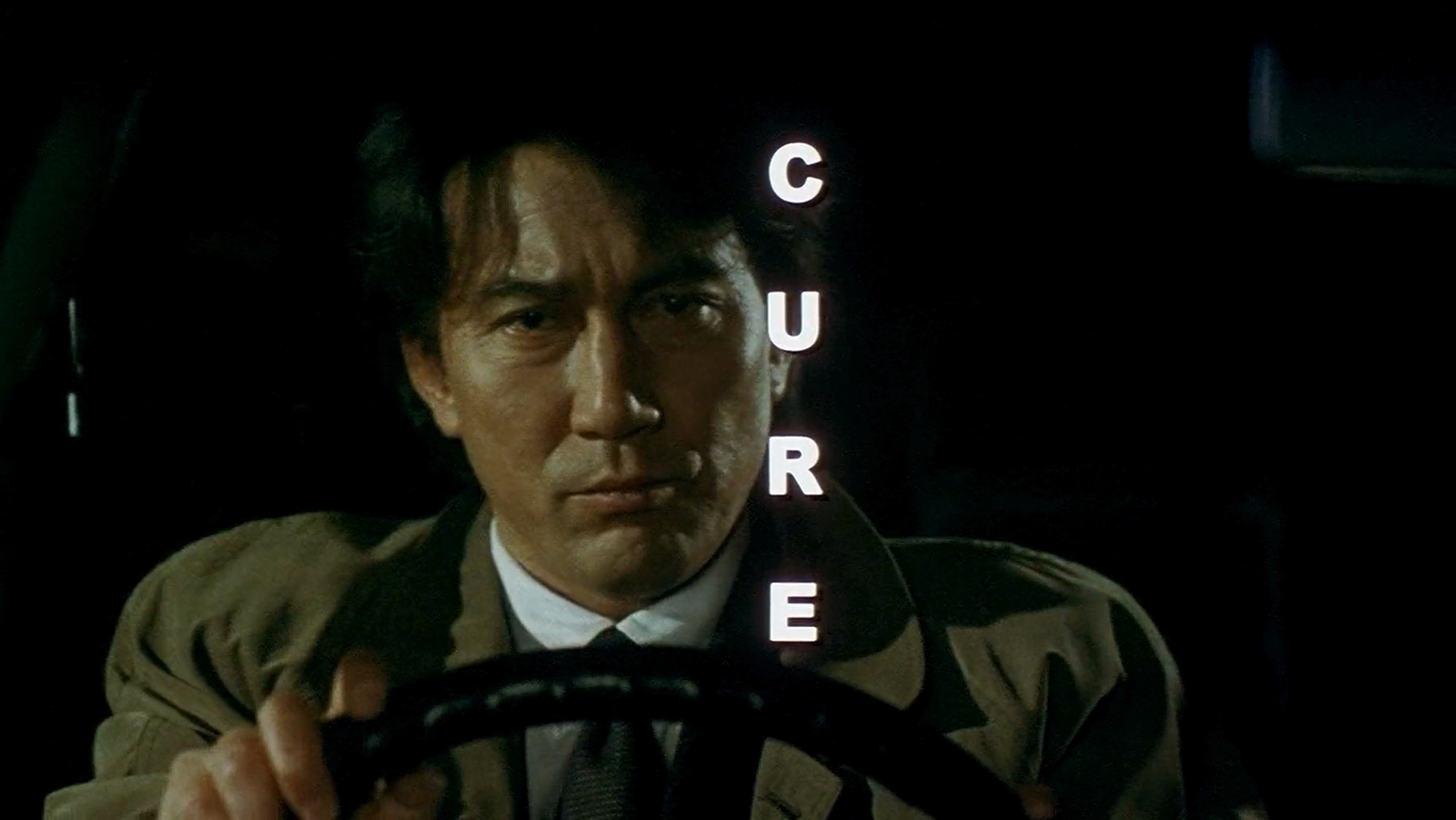

CURE, or Kyua, is a psychological horror film following Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) who has been plagued with solving a series of mysterious and excessively violent murders. Most puzzling is that there is nothing connecting the crimes together other than a deep ‘X’ carved across the victim’s neck and chest–and that the perpetrators have no explanation or memory of their vicious acts. When a man (Masato Hagiwara) who seems to be suffering from extreme short-term memory loss is revealed to be connected to these strange events, Takabe stops at nothing to uncover Mamiya’s methods and motives.

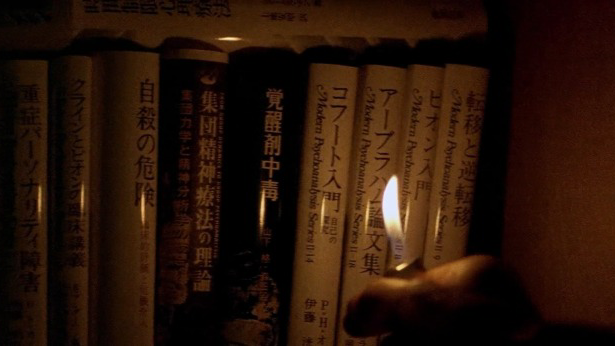

CURE draws inspiration from Franz Mesmer’s theories of animal magnetism, or mesmerism, which later became a theoretical background for hypnosis. Animal magnetism is, in my best attempt to summarize, the theory of the existence of a natural force present in all living things and that the flow of this force or, more aptly, the blockage of this flow could be cause of physical or mental ailments.

Mesmerism, as at it has been adapted for the story, is used by Mamiya as he pokes and prods, asking questions about the personal lives of the people he comes into contact with—a school teacher married to a housewife, a doctor who had an uphill battle in her profession, and (most importantly) an overworked detective whose wife has a sort of early onset dementia. What Mamiya unleashes after these interactions is what has been bubbling beneath the surface of the people who are being constricted and consumed by the obligations demanded by the society in which they live—particularly economic and gendered expectations, which are often so intertwined in capitalist societies. The pressures of being a breadwinner during economic stagnation. The pressures of breaking a glass ceiling. The pressures of taking care of a sick wife.

This isn’t just hinted at in the personal details of the characters but in other details throughout the film such as a man muttering obscenities at the dry cleaners, Takabe being told “don’t work too hard, you look more sick than your wife” and the fact that our perpetrator dwells in a junkyard—a literal industrial graveyard where products that once symbolized the economic boom of Japan now rust away.

And the question…”Who are you?”

Detective and husband are not sufficient answers to this question for Mamiya because we are meant to be more than our occupation (aka the method by which we sell our labor) or whether we are married (aka what role we are expected to play in a gender dynamic). However, anyone living in a capitalist society can attest to the fact that finding identity outside of our occupation is a grueling task. Mamiya goes so far as to taunt Detective Takabe, as well as Police Commandant Fujiwara, for not truly listening to his question.

“I’ll ask you again, Fujiwara of Headquarters. Who are you?”

“What do you mean?”

“You think about that.”

Mamiya is an agent of chaos, a complete disruption of capitalist repression, and could be seen as representing the fear of losing control when the reality is that, in a world where we cannot conjure an answer for who we are, none of us were ever completely in control.

It must also be discussed how I interpret the ambiguous and abrupt ending to this film and how I think the story of Bluebeard, introduced in the opening scene, factors into the equation. While it is most certainly foreshadowing the death of Takabe’s wife, another connection can be traced. To put it simply, the wife of Bluebeard’s overwhelming need to discover what is behind the door, to uncover forbidden knowledge, is what leads to the climax of Bluebeard. Pursuit of knowledge, as Mamiya suggests towards the end of the film when he accuses Takabe of letting him escape, is Takabe’s primary concern. He needs to understand how and why things are happening. Much like the wife inheriting Bluebeard’s castle after his demise, I interpret the final scene of CURE as Takabe continuing to unleash the hidden rage in others as Mamiya once did.

It is not a happy ending as in the fable, and it complicates what is meant by the film’s title. While the word ‘cure’ typically has a positive connotation, it can be defined simply as relief from symptoms of a disease or condition–and in the bleak world of Kurosawa’s CURE, unleashing animalistic violence seems to be the only ‘cure’ for the repressive condition and loss of identity caused by capitalism and the obligations caused by economic pressure.

CURE (1997) had me mesmerized, so to speak. The bleak and dreary sets are complemented by the haunting sound design, making stillness or the howling of wind a source of terror–in the same manner that I would ascribe to the wilderness in TWIN PEAKS. All of these ingredients, whether stylistic or thematic, I see explored even further in PULSE (2001), making me eager to continue to explore the masterful works of Kiyoshi Kurosawa.